On Grief as a Spiritual Practice. And a State of Being.

“…with grief, comes complete restructuring. It requires new movement, new places, new sounds and words and

ways of being to express what is happening internally.”

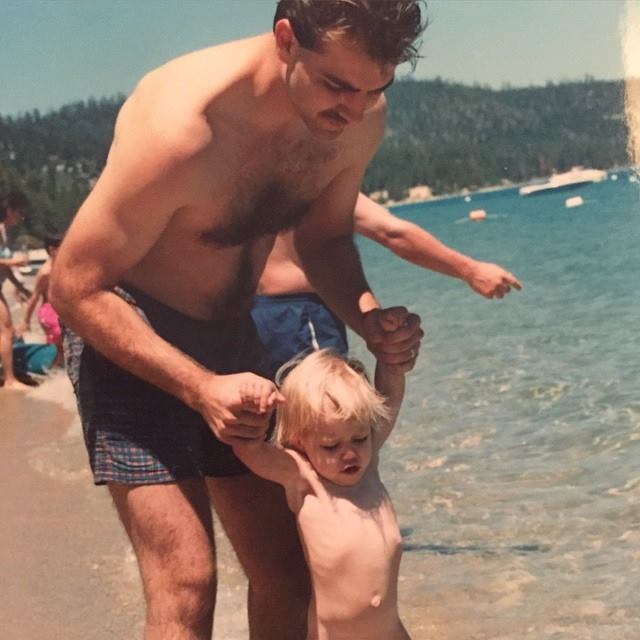

One singular memory of my time in Costa Rica with my Father often comes to mind for me. In it, I’m 12, and he’s teaching me how to dive under a breaking wave. I remember the delight of how it changed my experience – one moment, being bowled over 1, 2, 3 times by the crashing waves, the next, diving under a quiet blanket of wet, feathered foam.

Dad loved the ocean. He’d once upon a time even dreamed of becoming an oceanographer. He’s there in every memory of the cold Pacific hitting my face, again and again, never tiring of the back and forth between the waves to our warm towels – blue lips, leg goosebumps, and cold ocean air after the two-hour drive on the winding 128 West to Mendocino.

“Look, your mother is a fish!” he used to say to me.

Growing up in California, the ocean felt like a familiar piece of home – something I could predict based on eyeing the riptides and gauging the tide overall. Never have I needed someone else to pull me out of the foaming waves in the dark. Never since he taught me to dive into the waves has it ever thrown me 1, 2, 3 times over my own head until I come up coughing for air.

Mazunte was different; it changed that. Before coming, I had made a calculated decision to leave my comfort zone. I let a friend book me into a tiny little posada with cement floors and ripped, purple mosquito nets, a cold trickle of a shower, and half walls out to the hot, ocean air.

When I misjudged a tide for the first time, I’d run out in the middle of the night to look for bio-luminescent plankton. By the time I felt a friend grab my waist to pull me back to shore, I had been swallowing salt water by the mouthful, and the fear had hit me, stone cold.

“Sorry about that,” I said, catching my breath on the dark sand.

“Don’t be sorry,” he responded. “Being thrown like that is to be expected in waters like these.”

As we sat there together, I couldn’t help but think about how limited an ability we have to share our experience with the humans around us. While a friend and I can share the experience of an outside force together – say, a wave – there was no way for me to accurately express the feeling I had that I’d been drowning in my own life for a year and a half, overwhelmed with missing my father. I couldn’t express the relief I’d felt on some kind of subconscious molecular level when the rip tide hit, and my physical and emotional states became one.

“Oh, right. Drowning,” I thought, while my body got jerked underwater. “This is my life.”

In bed that night, I imagined what it would be like to show someone my grief with a heat map, to light up my broken pieces like the plankton I’d been searching for, like some kind of luminescent x-ray inside of me.

There’d be so much relief in that kind of clinical determination of my having been broken. I could take a quick photo with my iPhone, and show it at parties – “ah, see, right there above my gut is this spot that aches and echoes like a hollow drum since he died. And there, to the left of my sternum, the spot that I don’t have any words for – the place I go blank.”

Grief isn’t shared that way. Some have only ever dipped a toe in to feel her cold, foamy whisper. Others of us feel like we’re drowning, yelling to the others on shore. The feeling I get isn’t as much most people in my life don’t want to help me, as much as that that they can’t, because they’re swimming in a different tide. While I grope for air in the massive black curl of a current around me, they’re at home in the slow, rolling, California tide.

Suffering is not an intellectual exercise – something to talk through, or usher out with conversation. It’s much lower on Maslov’s scale than that – a dimension where simply finding expression is important. And in the finding, one begins to find relief.

For a year and a half, losing my Dad made me all the things I don’t want to be: unstable, reckless, angry, difficult, un-decisive. Rude. Emotional. Easy to hurt. As if it weren’t hard enough to be a single female in New York, let’s throw in the biggest possible Daddy issue a girl can have: not having one.

Halfway between my ugly tumble to the shore, I realized I’ve been fighting the nature of my grief.

In my mind, I envision myself sweetly making peace with what I lost. I’m “handling it.” I let it out in ways that benefit others. My struggle presents as productive and moving. I honor the sacred passing of my Father’s death “well”. I only share about it in appropriately moving moments, with sensitive people I can trust to share wisdom and comfort. I am a good griever. I grieve well.

I only have five memories within which my grief has been expressed this way:

- July 2015, two weeks after he died, I was overwhelmed with grief in my then-boyfriend’s kitchen in Williamsburg, BK, and cried for three hours solid with a water bottle on the floor alone. In the midst of it, I felt my father present (and crying with me) and, finally, asking if I could be okay with letting his spirit leave

- April 2016, the evening when I first knew I needed to leave aforementioned boyfriend, walking alone, en route back from a frozen mescal drink with a friend. I felt his presence beside me, letting me know that it was time to make the transition away, and that he was with me: a rare gift, to feel his sure approval of my decision when all I want, regularly, is his opinion in my life, and daily being met with silence

- The last week of May of this year, knee deep in the ocean on O’ahu, watching my brother, sparkling wet in the sun, hold my Dad’s ashes in both his hands and release them into the choppy, golden waves of the morning light – afterward, we ran on the beach laughing, shivering, hugging – and he said, “I know he’s here.”

- Sobbing through the movie James White

- The first week of November, high at a Bon Iver concert with my brother, Ryan, closing my eyes and feeling the rhythm of 33 “GOD” while he stood behind me. When I turned around at the end of the song, looking each other in the eyes with tears running down our faces

I have other memories.

- Screaming at my boyfriend (we’ll call him “S”) that I wanted to die

- Days in bed wishing I could die

- Months and months and nights after nights of screaming so loud the neighbors would come to complain. S, asking why our relationship was so difficult. Me, saying getting out of bed was difficult. Locking myself in his room alone for hours, refusing to speak

- One day, alone on the roof, afraid my own body might revolt against me and throw me off, because it didn’t want to be alive without my father – feeling its molecules, one by one, inch to the edge. Sitting in the middle of the roof, dead sober, with the world spinning, and willing myself to live – “live, live, live.” Come on, body.

- Crying through karaoke with a group of S’s colleagues in Chinatown, and cornering his partner to tell him he’d be responsible for making sure that his daughter never got assaulted – and telling him that when I did, my Dad hadn’t been there for me to call the next day, and hadn’t been awake when I got home. Later, throwing up while crying in the planters outside S’s apartment, too drunk to do anything but curl up in the snow until he came home to pick me up.

- Fighting in the street with a stranger twice my size after a D’Angelo show on Father’s Day

- Having an affair with someone who was well loved by someone else so I could feel more

- Screaming in Mexico at a college friend in the middle of his birthday week

I am so ashamed of some of these moments that I hate even writing about them here. Could I conquer my lament, I would, and mold it into an expression, like soft clay art set out to dry in the sun. I’d create a soft, inviting sadness that emanates from me.

There’s the other limitation I’ve been thinking about. I cannot get outside of my own body, to issue direction. If I could, I’d send myself to shows and concerts, destinations and conversations where I am helped to express the thing that has gone wrong and out of order – the great big blockage sitting in the way of my thriving, and get on with healing. I’d avoid the wreckage. I’d usher in peace.

“The word obliterate comes from the Latin obliterare. Ob means against; literare means letter or script. A literal translation is being against the letters,” Sheryl Strayed writes, in one of her famous pieces on grappling with death. “The strange and painful truth is that I’m a better person because I lost my mom young…[This] is the temple I built in my obliterated place. I’d give it all back in a snap, but the fact is, my grief taught me things. It showed me shades and hues I couldn’t have otherwise seen. It required me to suffer. It compelled me to reach.”

The turmoil is the tide I’ve been given – as full natural and native to this earth we’re living on as the waves in California. It is just as human, and legitimate, as joy. But It must be legitimized. And, after looking around me for over a year for someone else to do it, I’ve realized that normalizing my own dance with death is up to me.

I read once that the process of grieving is a spiritual practice – a kind of skill to cultivate, like meditation, or kindness, or an open mind. But I’m learning that the practice feels entirely different than the rest of those, because loss is not similar to accepting a gift, or a shift in seasons, or a job offer in a new city. It is, in fact, more like a rip tide than a small, quiet room.

Here’s where I wish our society would start with grief: when someone has it, they are a person in transition. They are not coping well. There is no way to cope well. They are simply coping as best they can as they learn how to express what often has no expression. They are in the school of the lament – a place so personal, so deep, that only through fighting their own way through the dark will they begin to find that they can swim where the waves throw them one, two, three times backward before they come up gasping for air and wondering what went wrong.

Here’s what I’m doing, whether society does it with me or not: I’m honoring the truth that, with grief, comes complete restructuring. It requires new movement, new places, new sounds and words and ways of being to express what is happening internally. These things don’t come easy. To find them, you have to save yourself from drowning, again and again and again until you get yourself back to shore. Nobody else can do it with you. And, there won’t be someone coming out to pull you home. It might get messy, and ugly, and you’ll probably flail before you figure out how to swim.

Don’t be sorry.

That’s to be expected, in waters like these.